By David Quigley

It begins with a polemic discussion one might overhear at a café. A contested dialogue between friends and rivals, with divergent interpretations, differing positions and antagonisms designing an abstract topography for reflection and action. Through the many disagreements, through the act of drawing abstract battle lines, discourse takes shape. What follows is a collection of moments in such a landscape, fragmentary remarks and research for an imagined conversation with Der Antist here elaborated as an introduction and polemic.

The conversation begins with a short excursion to Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the “war-machine,” then mentioning briefly the expressionist magazines Die Aktion (1911-1932), Der Gegner (1919-1924) (and the closely related Gruppe progressive Künstler) through Die Schastrommel (1969-1974) to land at Adorno’s uncompleted work Ästhetische Theorie. The goal is to both develop a kind of genealogy, a list of precursors and direct influences and then finally, with Adorno’s philosophy (but against his own “identity politics”), to make a call for a more complex notion of the polemic in art.

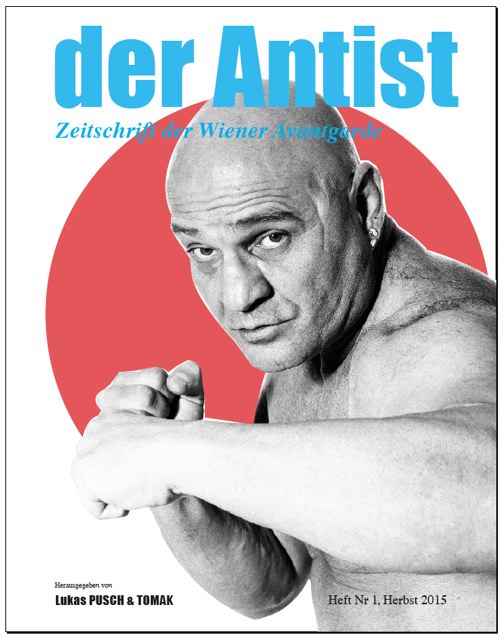

Cover der ersten Ausgabe des ANTIST

First Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the war-machine comes to mind: A social machine, an assemblage and constellation of people and ideas that forms in opposition to a given order. The war-machine (at least the affirmative Deleuzo-Guattarian understanding of the term) is anti-statist and nomadic. “The State has no war machine of its own.” The nomadic war-machine is a conglomeration of ideas and people that posits other forms of social and intellectual order against and as a kind of escape from the given, structured, administered cosmos of the sedentary. The war-machine is a social and theoretical concept that describes a nomadic movement against the “stratified” order of the polis with the promise of establishing a new anti-administrative, anti-statist relationship to space, to identity and power. The war-machine begins with the question: “Is there a way to extricate thought from the State model?” This is important. This is foremost an intellectual war of liberation, liberation of the mind, liberation of affects, liberation of practice from the determinate structures of a social field.

In contemporary terms this might entail calling into question given institutional structures of modern society, the triumphant historicist and institutionally secured version of reality that underlines the stratum of political legitimacy (Although this is where the whole project of the war-machine gets complicated: How to call into question a state nominally based on the universalist or progressive ideals? How to wage war against nominally democratic systems without resorting either to conservative calls to order or to revolutionary terror?).

Through the war-machine, distinctions are made that direct thought and practice towards other horizons (albeit carefully using the metaphor of the line of flight to avoid any confusion with teleology). But the question remains: how to define this conflict? How to direct the antagonistic (critical, dialectical, revolutionary. . .) forces without enclosing them in new kinds of ideology or formalisms of identity? Most importantly, how to avoid the minefield of microfascisms and ressentiment that haunt all forms of conflict? How to fight joyously?

The allegory of Der Kunstlump

In 1919, George Grosz and John Heartfield repeatedly attacked Oskar Kokoschka (who at the time was a professor at the Kunstakademie in Dresden) after he had publically called for an end to conflict after a painting (Bathseba am Springbrunnen (1555) by Rubens) had been damaged by a stray bullet during street fighting in the uprisings directly following the First World War. It is admittedly hard to take Kokoschka’s side in the debate. His seeming disregard for the people dying on the streets seems not only to lack concern for human life but also to be out of touch with the times in both aesthetic and political terms. Kokoschka:

“Ich richte an alle, die hier in Zukunft vorhaben, ihre politischen Theorien, gleichviel ob links-, rechts- oder mittelradicale, mit dem Schießprügel zu argumentieren, die flehentlichste Bitte, solche geplanten kriegerischen Übungen nicht mehr vor der Gemäldegalerie des Zwingers, sondern auf den Schießplätzen der Heide abhalten zu wollen, wo menschliche Kultur nicht in Gefahr kommt.”

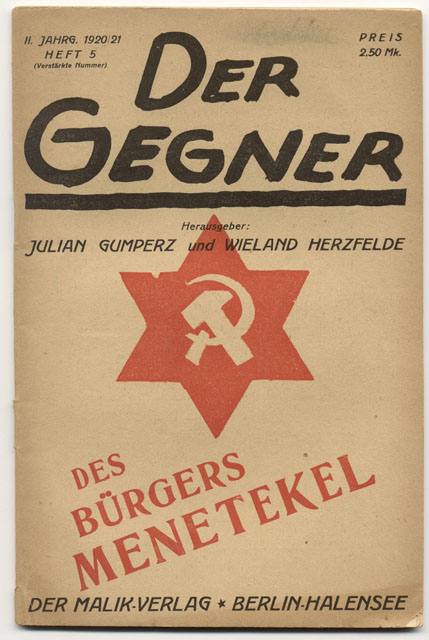

Der Gegner

While there were many polemic responses to Kokoschka, the most extreme was voiced by Grosz and Heartfield in Der Gegner. They were not only taking on Kokoschka. This was also a question of rethinking an entire ideology of culture, especially the art object and most of all what role it could play in society.

“In den Staatsgebäuden zur Pflege und Erhaltung der mittelalterlichen Inventare und Gebilde, eines Stabes überflüssiger Kunstbeamten, alles toten, heutigen Lebensbedürfnissen zuwidersprechenden Gerümpels, Geschreibsels und Gemales, das bestenfalls nur historischen Nachschlagewert hat für Idioten und Nichtstuer, die die Dokumente der menschlichen Dummheit, bis in die greiseste Vergangenheit greifend, preisen zu müssen glauben, hängen die verstaubten ‘Werke’ der Rubens, Rembrandts, die für uns heute nicht den geringsten Lebenswert mehr bergen. (…) Wir richten an alle, die noch nicht genug verblödet sind, die snobistische Äußerung dieses Kunstlumpen [Kokoschka] gutzuheißen, die dringende Bitte, energisch Stellung dagegen zu nehmen. Wir fordern alle dazu auf, denen es nebensächlich ist, daß Kugeln Meisterbilder verletzen, da sie Menschen zerfetzen, die ihr Leben wagen, um sich und ihre Mitmenschen aus den Klauen der Aussauger zu erretten.”

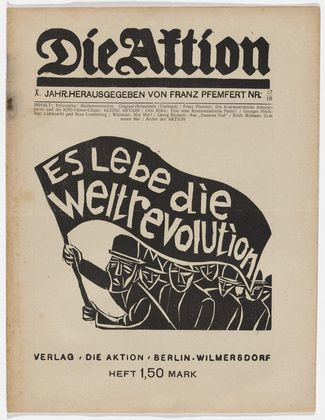

Die Aktion

Franz Seiwert in Franz Pfemfert’s Die Aktion also joined in:

“Es sind ein paar Löcher in Rubenssche Schinken gekommen! Hilfe! Die Kultur ist in Gefahr! Wo soll sich der feiste Dickwanst nun seinen Kunstgenuß holen in dieser fleischlosen Zeit? (. . .) Genossen! Fort mit der Achtung vor dieser ganzen bürgerlichen Kultur! Schmeißt die alten Götzenbilder um! Im Namen der kommmenden proletarischen Kultur!”

But not everybody on the left was prepared to attack Kokoschka (and by default bourgeois culture) in these terms. The question of the destruction of art (the Dadaist and Futurist call to begin anew, tabula rasa) eventually became a fundamental conflict between artists and the official Communist Party rhetoric of Die Rote Fahne where, for example, August Thalheimer dismissed the polemics of the Dadaists as a sign of the decadence of the “declining and decaying bourgeoisie.” The Rote Fahne and the KPD’s position mirrored the official position of Lenin and Trotsky (although Trotsky would famously later recant it) and the official version of Proletkult, which all had come out to denounce futurism and formalism. . .

But what is the “moral” of this story you might ask? The reason we mention these artists and magazines in this context is clear. But why this particular story? First of all there is a conscious and explicit connection between Lukas Pusch’s own work and that of many of the Expressionists. Second, one could claim that this debate, albeit in very different terms, still remains unresolved (the debate defined on varying sides by political activists, post-painterly monteurs against (figurative) expressionist painters. . .with the missing position of Socialist Realism ready to be taken up again!). Finally, this is the perfect context to imagine Der Antist. Provocation, controversy, taking pronounced positions in debates. . . all brought up within the public sphere as discourse and as aesthetic position.

Quite frankly, I do not know which side Der Antist would have taken in this dispute. Aesthetically closer to Kokoschka (and to Socialist Realism), in spirit closer to Grosz and Heartfield. However, the very fact that we tend more to side with Heartfield, Grosz, etc. leads me to think Der Antist would take the side of Kokoschka but of course. . . with the distance of history, either side seems viable. . .

Preludium and Fugue:

On the necessity of governments in exile: Günther Brus left the gallery then the country. But first he had to bring everything to the point of crisis.

Günther Brus’s first action entitled Ana (his wife’s name) took place in Otto Muehl’s apartment in November 1964. Brus painted all of the objects in one room white. He then rolled around the room with his body itself rolled up in white cloth. At some point he began pouring black paint onto the objects in the room. He then began painting his wife, whom he thought of as a kind of “lebendiges Gemälde.” Kurt Kren documented the action with his 16 mm camera.

His second action was the famous Wiener Spaziergang from 1965, where he intended to walk from Heldenplatz past the Dorotheum to St. Stephen‘s Cathedral but was stopped by the police who arrested him for disruption of public order. In leaving the space of the Galerie Junge Generation where the exhibition he was participating in was taking place, Brus placed his work outside of the protected space of mere experimentation. This displacement within the spatial order of the city very quickly became a threat. Today we are prone to claim that the severity of the response was due to the conservative, post-war, post-Nazi conditions of the early 1960s in Vienna. This is definitely partly true. But this kind of provocation is still possible—and not even only with more radical statements. The question of the place where this provocation takes place remains at least as important as it did nearly 50 years ago.

After the Kunst und Revolution event at the University of Vienna in 1969 where Brus was afterwards sentenced to 6 months in prison, he was forced to leave Austria.

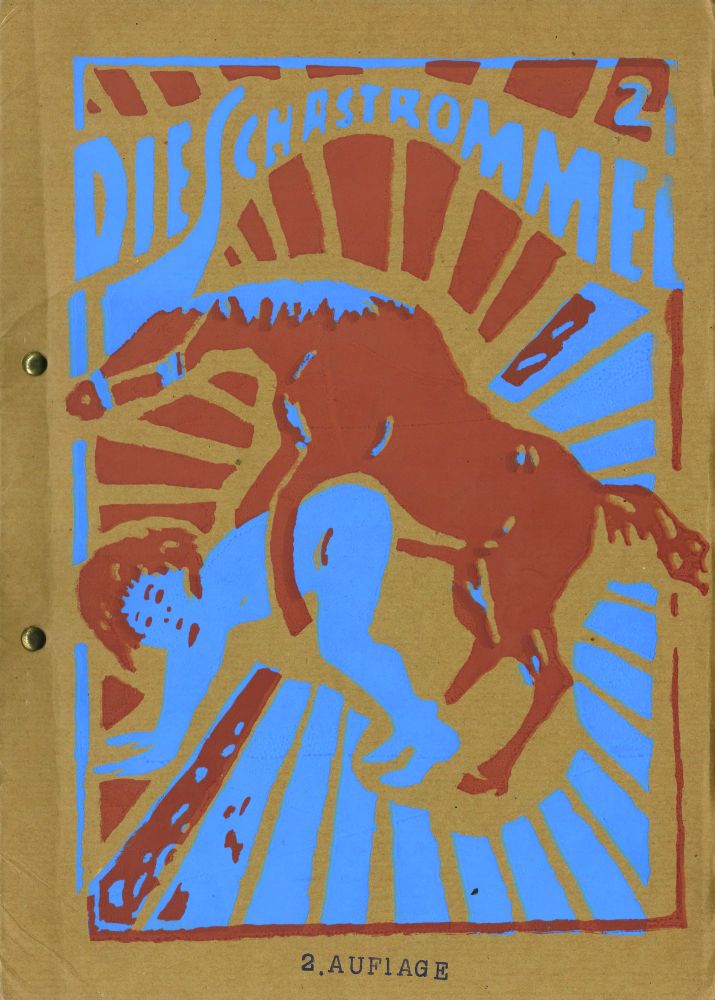

This forced exile eventually lead to the publication of Die Schastrommel (and later Drossel. . .and much, much later to the publication of Der Antist. . .). In Oswald and Ingrid Wiener’s restaurant “Exil” in Berlin, a project was begun that would bring together the various actors in a common project as the “Organ der Exilregierung”. Günther Brus recalled its foundation:

“Im Fluß der Getränke wurde die Idee geboren, die ‘österreichische Exilregierung’ zu gründen. Mit Sitz in Bolzano. Ministerposten wurden keine vergeben, sondern jeder war ein Kaiser. Oswald Wiener ‘Kaiser für Militärkaiser’, Gerhard Rühm und ich ‘Kaiser für Inneres und Äußeres’. Und im Strome der Getränke gründeten wir das Organ der Exilregierung. Wir ergingen uns in Titelvorschlägen, als Rühm ausrief: ‘Schastrommel!’. Schon etwa drei Wochen später besorgte ich per Siebdruck den Umschlag, und ein katholischer Jugendverein druckte den Inhalt in einer Nachtschicht.”

Die Schastrommel, Zentralorgan der österreichischen Exilregierung von Günter Brus

Die Schastrommel was a way to establish a collective practice and exchange of ideas outside and in explicit contradiction to Austria and the Austrian state:

“die intolerante haltung der österreichischen behörden erklärt sich aus der faschistischen vergangenheit des landes. der alpine faschismus sitzt jedem österreicher tief unter der haut. da österreich als ein von den nazis okkupiertes land gilt, konnte der österreicher keine schuldgefühle entwickeln, die ihn genötigt hätten, sich mit einer faschistischen verseuchung auseinander zu setzen. dörflerische engstirnigkeit, selbstgefälligkeit, stolz auf monarchische erbe wie spanische hofreitschule, staatsoper und schifahren machen den rest.”

Günter Brus, Oswald Wiener, Gerhard Rühm, Hermann Nitsch and Otmar Bauer. Peter Kubelka, Kurt Kren and Marc Adrian. All published in Die Schastrommel. Outwardly the Viennese film movement and Marc Adrian’s work might not share much with the Actionists. But there were numerous cross-overs both personally and professionally. But what bound them together most was their need to create new forms of art understood as new forms of living and working together. The Exilregierung was a nation within a nation (within a nation), a kind of independent collective reminiscent of Jonas Mekas’s film from 1996 ironically entitled Birth of Nation:

“Why Birth of a Nation? Because the film independents IS a nation in itself. We are surrounded by commercial cinema Nation the same way as the indigenous people of the United States or of any other country are surrounded by Ruling Powers. We are the invisible, but essential nation of cinema. We are the cinema.”

This collective practice as transformation of life through art conceived in the most basic way possible (here also thinking of the non-evolutionary understanding of “primitivism” so important for Picasso, Carl Einstein, the Surrealists, etc. which Deleuze and Guattari arguably, passing through Pierre Clastres, translated into the notion of the nomad) is the binding force for these groups. The indigenous peoples (those leading their lives between the state apparatus and capitalist megastructures) are the partially visible collectives of ‘nation-builders’ in exile. . .

Conclusion

Adorno wrote in the Aesthetic Theory: “All artworks, even the affirmative, are a priori polemical.” “By emphatically separating themselves from the empirical world, their other, they bear witness that the world itself should be other than it is; they are the unconscious schemata of that world’s transformation.” It is this polemic core of artworks, their mark of “distancing,” the “friction of antagonistic elements”, the artwork’s “refusal of reconciliation” that lies at the heart of Adorno’s understanding of art’s position within modern society as something that shows what could become of the world.

The polemic of art is an “emphatic separation” from the “empirical world”. This could mean a lot of different things. First of all the most basic: this thing before your eyes, this mixture of colors and lines on canvas is more than sum of its parts. This thing is something other than what it appears to be. Second, and slightly more paradoxically, the disjunction of art implies something that is both intelligible and refuses direct identification. The artwork is both difficult even hermetic and at the same time understandable. Like communication it must share in a common field of comprehension, but at the same time it must somehow differentiate itself in its articulation from whatever is NOT art: the polemic of an artwork is that which differentiates it from other forms of communication. In this sense the polemic is similar to Viktor Shklovsky’s theory of defamiliarization [остранение (Ostranenie)]. Poetry and art must be distinguishable from other forms of language. Third (and most importantly), art’s polemic must be seen both on a formal level and the level of philosophical aesthetics, both as an art object and as part of a more complex ‘battle’ or war (polemos) with the constellation of ideas constituting identity and the organization of the world. The artwork becomes a means to both imagine a new historical situation and to break through the “illusion of constitutive subjectivity.” This artwork hints at new ways of conceiving experience in philosophical and socio-political terms. It is here that the polemic of the artwork resembles the polemic of the Marxist. The “world itself should be other than it is.” The artwork challenges the reigning conditions of experience with a new means of differentiation between subject and object beyond mere identification (As a disruption of the relationship between subject and object, this is not merely a correlationist game. The very goal is to go beyond any reconciliation, beyond any correlation between subject and object).

With Adorno, the artwork becomes a kind of tool for overcoming the confines of historical determinism and for breaking through, or rupturing the illusion (Trug) of constitutive subjectivity. The formal qualities of art become a means to resist the given situation, in terms of subjectivity and in terms of collective experience. “The unsolved antagonisms of reality return in artworks as immanent problems of form” with irreconcilability, dissonance, nonidentity all referring to aspects both of artworks and the conditions of existence. “Rather than imitating reality, artworks demonstrate this displacement to reality.”

It is here, in taking “displacement, irreconcilability, dissonance and nonidentity” seriously that one could imagine a different Adorno than what we have been accustomed: An Adorno undermining metaphysical identity but not merely through philosophical gymnastics and dodecaphony, a queer Adorno, a revolutionary jazz and critical pop-loving Adorno, a monster Adorno breaking up the conventional subject and its relations with the inner and outer world (this is a kind of crazy jump. . . I know, but just imagine it for a second!!!). In both taking Adorno’s argumentation seriously and imagining a radically other Adorno (imagine if Hector Rottweiler aka Adorno had one night alone in his Faustian Studierzimmer accidentally tuned into to Joachim-Ernst Berendt’s Jazztime Baden-Baden and heard John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. . .), I hope to provoke a kind of other Antist waging its war against the administrative arm of “culture” and the many fascisms (both micro and macro), but leaving behind the petty concerns of modern imperial court life in Vienna (on a journey to Novosibirsk!). Dispelling with the illusion of constitutive subjectivity means being willing to turn against one’s own metaphysical foundations, engaged with a battle with what was once solid, setting a course towards a yet undefined horizon in art and experience.

1 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. [Mille plateaux: 1980] Trans. Brian Massumi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987, p.355.

2 Ibid., p.374.

3 Wolfgang Asholt and Walter Fähnders (ed.), Manifeste und Proklamationen der europäischen Avantgarde (1909–1938). Stuttgart-Weimar: Springer-Verlag, 2016, p. 204

4 John Heartfield und Georg Grosz, “Der Kunstlump (Oskar Kokoscka)”. In: Der Gegner, Volume 1, Number 12, December 1919, p. 48.

5 Franz Seiwert, “Das Loch in Rubens Schinken,” in: Die Aktion. Jg. 10, Nr. 29/30, 24. Juli 1920, pp. 418-419.

6 Brus: “Am Tag vor dieser Ausstellungseröffnung mit Aktion und Diskussion beschloß ich, dem Kompromißcharakter dieses Unternehmens gewissermaßen vorzubeugen, um meinen künstlerischen Absichten mehr Eindeutigkeit zu verleihen. Man könnte sagen, die zwittrige Aktivität dieser Galerie trieb mich von den Rattenkellern auf die Straße. Ich beschloß, als gleichsam lebendes Bild durch Wiens Innenstadt, vorbei an etlichen historisch bedeutsamen Bauwerken, zu spazieren.” ( https://www.museum-joanneum.at/neue-galerie-graz/sammlung/sammlungsbereiche/bruseum/guenter-brus )

7 Günter Brus, Das gute alte West-Berlin. Wien: Jung und Jung, 2010, p. 19.

8 Günter Brus (ed.): Die Schastrommel, N. 2, p. 20.

9 Jonas Mekas on Birth of a Nation (1996) an 81 minute movie with music by Richard Wagner, Hermann Nitsch and Jean Houston with a lecture on Parsifal: “One hundred and sixty portraits or rather appearances, sketches and glimpses of avantgarde, independent filmmakers and film activists between 1955 and 1996.”

10 Adorno, Aesthetic Theory. Trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997, p.177.

11 Ibid., p.177.

12 Ibid., p.177.

13 Theodor W. Adorno, Negative Dialektik. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, p.10.

14 Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory. p.6.

15 For Adorno, there is a lot at stake in art (one might argue too much. . . to which I would agree, yes, he demands too much. . . but that is the essence of art: one must always demand more of art than it can actually offer).

16 Aesthetic Theory, p.181.